Splitting Fields

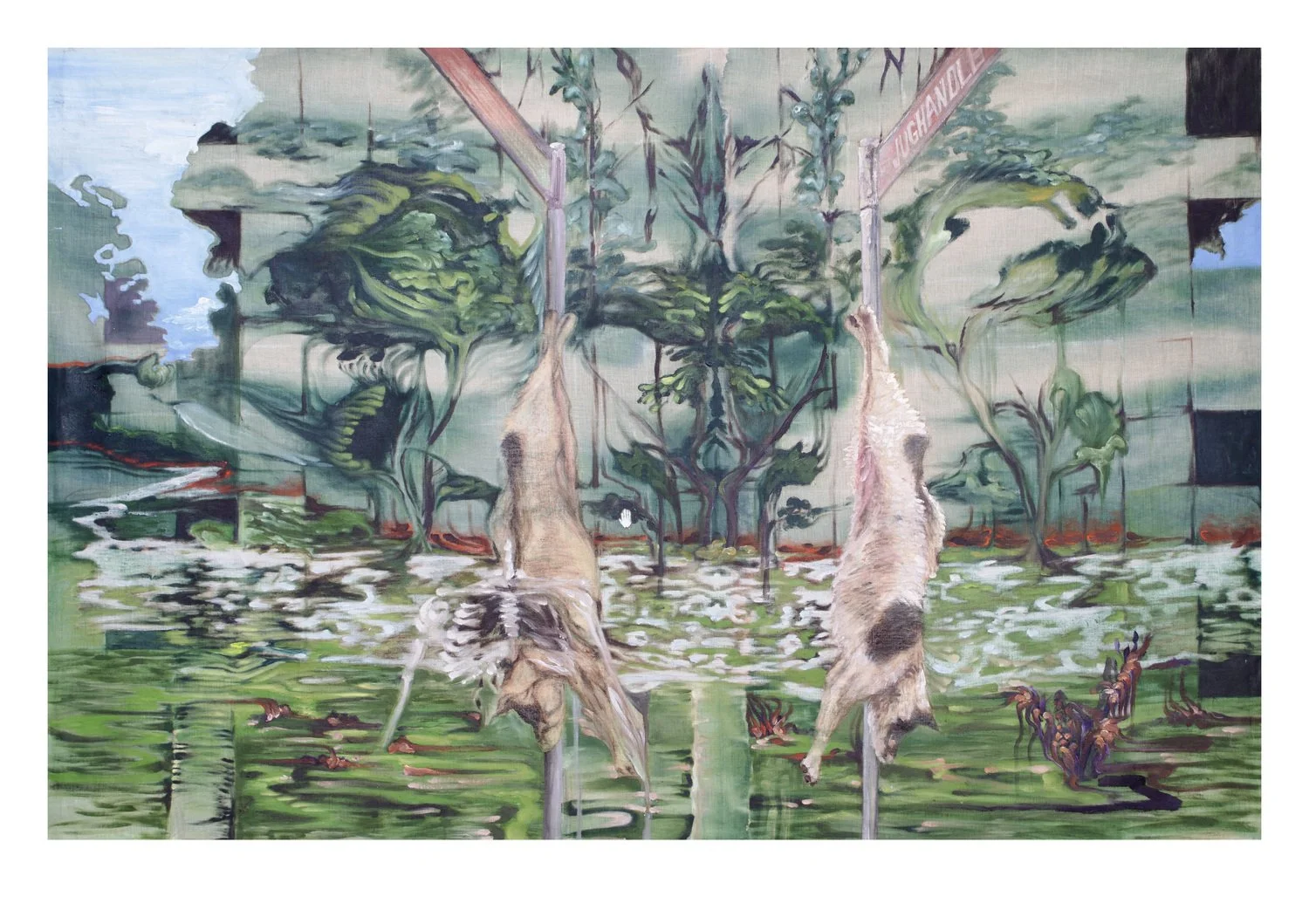

I first saw the dog fences as a kid. Common as the early spring lambs lying frosted in the paddock, born too close to winter. I took this photograph near my hometown of Bendoc a few days after a spring snow, through the sharp warm midday sun the air was crisp enough to hold the snow in low pockets.

Days like that are the quietest, lest somebody question their impossibility.

This wild dog was killed by a local, he matched me in body weight and was disarmingly beautiful. Most likely a border collie bred with wild dogs, possibly an abandoned mutt puppy hardened by the wild. They're strung up like this in paddocks and alongside roads all around far East Gippsland and the Snowy Mountains. They serve as a warning to people that they’re around, best they keep their kids and animals inside at dusk and dawn, also in the hope that the public crucifixion will ward off other dogs coming into the area. They're trophies too.

On the school bus we’d see fences of them, stretching on for ages. Their carcases in various stages of decay sparked debates about cruelty and morality in agricultural practices and the wider world. Conversations that made my head whirl as a little girl, as I tried to grapple with the prospect of violence being a byproduct of good intention: that evils don’t always stem from malice. There are many things that aren’t straightforward in the slaughter of harmful or introduced species, especially those as dangerous as a hungry wolf, and as beautiful as a best friend.

These dogs have appeared in different forms throughout my practice, symbolic of the notion of two contradictory ideas co-existing in ones mind. To feel love and pain at the same time, forgiveness and betrayal, disgust and understanding concurrently. I think it’s something that highlights our flawed and layered nature as humans. To remember that all things are contextual and have a lineage beyond what we see on face value is a concept that helps me stay away from extremist views or going down rabbit holes in any one direction.

In psychology this concept is cognitive dissonance; and where one shields us from seeing that the pure existence of the dilemma is inherently wrong, George Orwell calls it double think. They speak to the double standards that we live by to uphold morality around our political identities, and the myriads of ways that we shield ourselves through reasoning to protect ourselves from the reality of suffering that occurs out of view. They speak to the violence that we are unavoidably complicit to by existing at the top of the food chain – nevertheless in the first world.

Artist Biography

Bonnie-Jean’s work functions to explore queer perspectives and autobiographical narratives around morality and place. It exists in a sustained state of experimentation and repetition: Revisiting her childhood home to mine for context and memories, photographing her partner to document her transition, and tracing parts of her body and photographs.

She treats the surface more like a textile than a painting: Folding, beading, and dyeing it with ink. Rubbing wax into areas to create resists and using salt to encourage the pigment to dry in interesting ways. Glass, wax, salt, flax, cotton, oil, water and pigment all speak to a type of alchemy. For Bonnie, painting is deeply rooted in a fixation with analogue process and construction. She chases relationships between the subject, symbolism and materials: Following patterns made through the dying process, arranging images to emphasise them and embellishing parts of the narrative she wants to romanticise.

She relates fabric to a body and to the stratum of the earth, all vessels that bare traces of their lives, all that have a penetrable surface layer, and all fixed to a path of least resistance. An ongoing practice grants permission to spend time in these material and conceptual indulgences. In a culture so hell bent on productivity and action, that can be difficult to do without guilt, so paintings make it tangible.

Bonnie-Jean Whitlock was raised in Far East Gippsland; she currently lives and works in Naarm/Melbourne. She completed a Master of Fine Art at RMIT in 2023 and was a recipient of the Evan Lowenstein Arts Management Prize.